June 22, 2018

Taking it to the extreme: UCalgary scientists team up with ultramarathoner for research study

Despite being able to eat a pound of bacon in one sitting or devour a box of ice cream cones, elite runner Dave Proctor says he’s in the best shape of his life. Proctor currently consumes 10,000 calories per day and runs up to 250 kilometres a week to train for his next challenge: a 7,200-kilometre, 66-day run across Canada with a goal of raising $1 million for rare disease research.

At the age of two, Proctor’s son, Sam, now 9, was diagnosed with relapsing encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia, a rare disease that causes lack of balance, impaired co-ordination and slurred speech. The disease is known to affect only four other people in the world.

“One in 12 Canadians are affected by rare diseases — that’s not all that rare,” says Proctor. “We need to conduct a lot more research, and researchers need these dollars to be there in order to apply for grants.”

Proctor's run raises funds, contributes to science

With guidance from his team of managers and advisers, Proctor will be running an average of 108 km a day from Victoria, B.C. to St. John’s, N.L. At multiple stops along the run, Proctor will also work with a team of researchers from the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM) and Alberta Health Services, who will study his body to better understand the health effects of ultra-endurance sports.

“Ultramarathon running and other extreme forms of prolonged strenuous exercise are rapidly gaining popularity,” says Dr. Aaron Phillips, PhD, member of the Hotchkiss Brain Institute and Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta. “We, as a scientific and medical community, need to catch up and be able to understand the effects of these sports. Knowing more about how the body adapts to ultra-endurance sports will allow for the development of better training programs as well as safety guidelines for participants.”

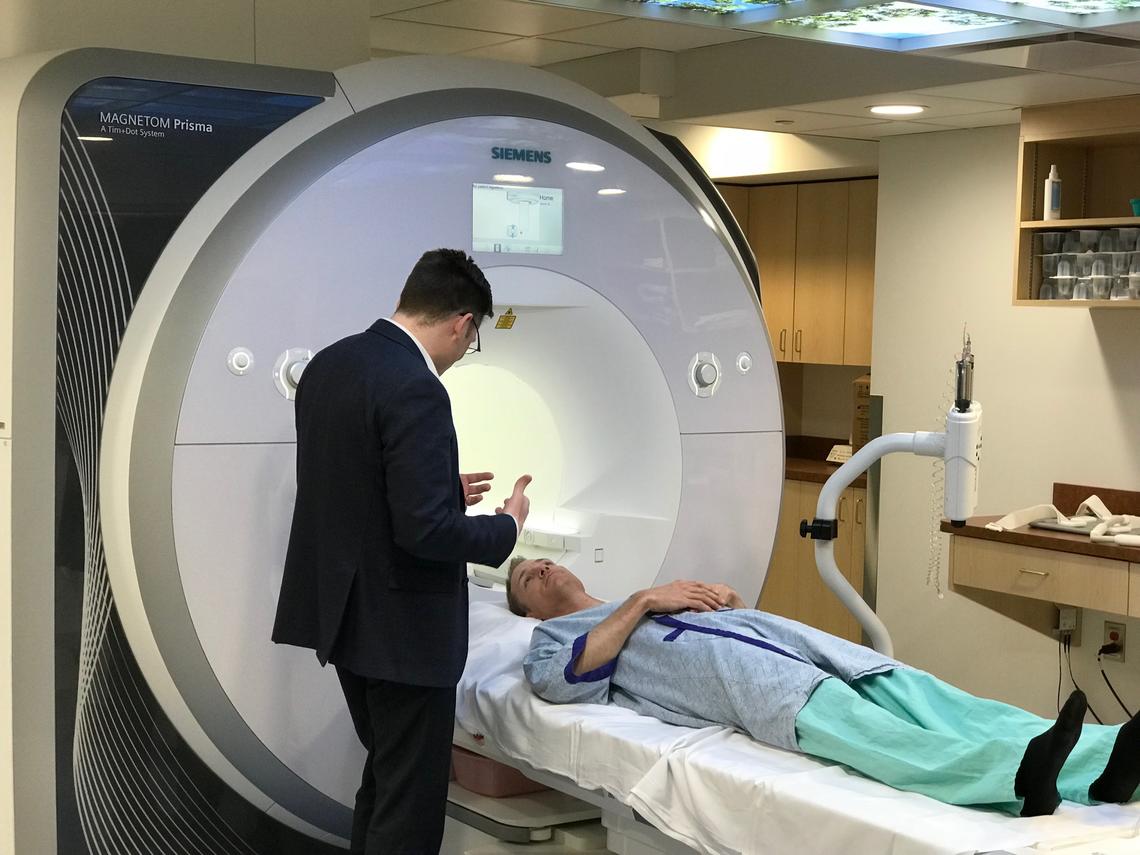

James White speaks to Dave Proctor as he prepares for an examination in the cardiac MRI.

Kelly Johnston, Cumming School of Medicine

Aerobic health, fitness assessed

Phillips and his team at the Clinical and Translational Exercise Physiology (CTEP) Laboratory, a state-of-the-art facility within the CSM dedicated to researching exercise physiology in health and disease, will assess Proctor’s aerobic health and fitness.

Proctor will undergo the VO2 max test, a gruelling fitness assessment done on a treadmill where the speed and incline gradually intensifies until the individual hits their anaerobic threshold — the point in which the body is no longer able to convert oxygen into energy quickly enough and must start supplementing with energy from reserve sources.

“We think Dave’s anaerobic threshold, either genetically or through training, is much higher than the average person,” says Phillips. “He’s a very unique individual.”

The CTEP Lab will also monitor Proctor’s vascular structure — the network of arteries and veins that transports blood, oxygen and nutrients throughout the body — by taking ultrasound videos of blood vessels in Proctor’s arms and legs.

Lab examines how the body adapts to extreme exercise

The lab of Dr. Antoine Dufour, PhD, will examine proteins in Proctor’s blood to look for clues about how various systems within the body are adapting to the prolonged physical exercise.

“If the heart or lungs are pumping too much or too little, it will leave a signature behind in the proteins,” says Dufour, member of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health. “What’s left behind in the blood is one way of piecing together what’s happened throughout his body.”

Dufour will collect blood samples from Proctor throughout his run and process them through a mass spectrometer, an instrument capable of analyzing tens of thousands of proteins within only two to three hours.

Rare opportunity to track heart changes

The Foothills Medical Centre’s Stephenson Advanced Cardiac Imaging Centre, led by Dr. James White, MD, will be responsible for tracking changes in Proctor’s heart. Using cardiac MRI, the researchers will monitor the size, shape and function of the heart, as well as detect any signs of inflammation or damage.

“We can measure the amount of fibrosis (scarring) or collagen within the heart muscle,” says White. “By doing this, we’ll be able to understand if, after repetitive strain, the heart adapts transiently or by laying down collagen. That’s a more permanent change.”

The scientists will also generate 4D cardiac models of heart function and blood flow to more accurately see how changes in the heart affect its ability to pump blood throughout the body.

“This is a very rare opportunity,” says White. “Not just because Dave is doing something extreme, but because of his willingness to participate and be evaluated throughout the course of this journey.”

Proctor won’t be the only study participant. The research team also plans to recruit 10 ultra-marathon runners — those who partake in races longer than a traditional 42.2-kilometre marathon — as well as 50 healthy volunteers.

Dr. White and elite runner Dave Proctor.

Kelly Johnston, Cumming School of Medicine

Integrated approach offers global understanding

“There’s never been a study like this in this field,” says Phillips. “There have been several studies on ultra-marathons, and some have focused on cardiac, on cognition, or on vascular, but there’s never been a comprehensive study on prolonged strenuous exercise, especially not one on repetitive prolonged strenuous exercise.”

White adds that the integrated approach of this study, which brings together scientists with different backgrounds and specialties, will allow the researchers to get a truly global understanding of Proctor’s health and function.

“There are very few places that have this unique combination of skill sets,” he says. “The resources that we have here at the Cumming School of Medicine and Foothills Medical Centre are really outstanding. It’s wonderful that we get this opportunity to show that.”

Study participants needed

Proctor, who begins his epic run across Canada on June 27, adds he’s excited to be part of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to contribute to scientific knowledge while fundraising for the Rare Disease Foundation.

“I’m not going to be doing this (kind of run) again,” he says. “But I wanted to make my body and myself available to science. It’s an excellent way of giving back to a community that I’ve received so much support from.”

Interested study participants can contact Jackie Flewitt at jacqueline.flewitt@ahs.ca or call 403-944-2541.

Aaron Phillips is an assistant professor in the Departments of Clinical Neurosciences, Cardiac Sciences and Physiology & Pharmacology and member of the Hotchkiss Brain Institute and Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta.

James White is the director of the Stephenson Advanced Cardiac Imaging Centre; an associate professor in the Departments of Cardiac Sciences, Radiology and Medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine; and a member of the Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta.

Antoine Dufour is an assistant professor in the Department of Physiology & Pharmacology and member of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health.