March 29, 2021

What The Curse of Oak Island is teaching us about treasures

Never — and this bears repeating, never — did a hesitant PhD student, who would go on to become a geoscience professor at Acadia University, dream he’d be digging for treasure on a cursed island off the east coast of Nova Scotia. Never.

Or that his professional expertise would net him an enviable role in a reality TV show seen by close to three million viewers every Tuesday night.

- Photo above: Fans who watch The Curse of Oak Island will recognize these familiar faces, from left: Craig Tester, Marty Lagina, Rick Lagina, David Blankenship, Alex Lagina, Steve Guptill and Ian Spooner.

But stranger things have happened on the wee island resembling a question mark that provides the setting for the History Channel’s long-running reality TV show The Curse of Oak Island. Its cryptic shape is telling, insist fans who have puzzled over Oak Island’s baffling treasure tale since . . . well, the late 1700s. The story goes that in 1795, Daniel McGinnis and two buddies were larking about on the island when they found a clay-lined shaft and two floors of oak logs. And so they began digging. And digging. And every 10 feet, they struck another log platform until, at a whopping depth of 98 feet (and many years later), the area flooded. That’s when the three men gave up.

Of course, fans of the TV show, now in its eighth season, know this chapter through the stories that two current-day treasure-seekers, brothers Rick and Marty Lagina, share week after week. And, because this is the History Channel, experts such as UCalgary alumnus Dr. Ian Spooner, PhD’94, appear to help solve one of the longest-running treasure hunts on the planet. Theories of what may lie hidden in this formidable underground complex range from Inca gold and the booty of infamous pirate Captain Kidd, to even the Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail.

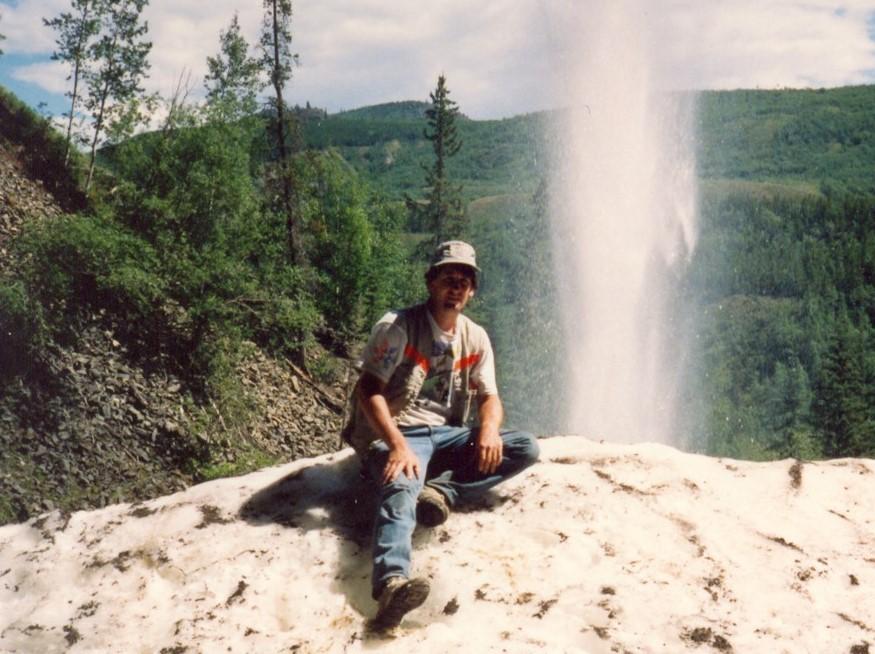

Ian Spooner, back in the day, while working on his PhD at UCalgary.

“I suppose I’ve become the swamp expert,” says Spooner with a laugh. The environmental geoscientist at Acadia attributes his satisfying career to a chance encounter he had with UCalgary geology professor Dr. Gerald (Jerry) Osborn, PhD. At the time, Spooner was working in the retail shop at Skiing Louise, “but had a feeling there was more academic time left in me . . . and then I really liked the research that Jerry was doing and the project he proposed to me so I left Lake Louise to work under Jerry for four years and got my PhD.”

With a busy summer graduate research program, Spooner could not commit to being a researcher on The Curse of Oak Island and had to turn down the first inquiry about being involved. “But in 2019 my schedule was a little more open and that’s when I realized that Oak Island is a great environment where science and a story have been stirred together,” he says.

In these times, when so many people don't understand or trust science, whether it's climate science or social science . . . well, narrative stories can be critically important. And so I hope that people say, ‘Hey, science is helping find that treasure — this is kind of cool.’

For more than 20 years, Spooner has worked with various communities and believes “that, in many ways, the stories and the narrative that inform a site where you’re working can be as important as the data that you’re pulling out.”

So, what data or “treasures” have the Laginas, who were digging on Oak Island long before the producers of the reality TV show discovered them, actually extracted?

Discoveries prompt even more questions

So far, their bounty has included a latch (off a chest, perhaps?), a garnet brooch (could it be one of Marie Antionette’s lost jewels?), buttons and coins, an old ring-bolt, iron spikes, a stone carved with a coded message, and a chunk of coal that Spooner declares in one episode is “one of the most significant finds yet.” That’s because, while the other artifacts might have more of a “buried treasure” esthetic, the coal is significant because the audience is left to ponder: where did the chunk originate and how did it get there?

And then there’s the episode in which Spooner himself is deep in the swamp, splattered with muck, when his steel probe clinks against something. The team keeps probing and clinking until they unearth a buried stone structure that is at least six by 18 metres long, which then appears to connect to a stone road.

“Something went on there that...,” Spooner says, stopping for dramatic effect, “in my personal opinion, is probably bigger than treasure. What’s there is an important part of Nova Scotia’s and likely Canada’s history.”

Sure, the focus might be on what’s affectionately been dubbed the Money Pit (where believers maintain that £2 million lies buried), but there are other shapes in the shadows that, for Spooner, are just as intriguing. Why was a road built across a swamp in the 1700s? Back then, most of the boats in this area were military vessels and belonged to the British, French and Spanish. If you wanted to get to shore, you had to build something you could drag your boats on . . . was that, indeed, the purpose of the road?

If Spooner and his students (who have been able to aid in the research) have questions, they’re certainly not alone.

Everyone wants to solve the mystery

“I get emails every day from people with theories they want the research team to consider,” says Spooner. “I think that's one of the most gratifying aspects to this project — emails that say, ‘My dad and I have been interested in Oak Island for the last six years and here’s what we think . . . ’ It seems that families connect over the mystery . And, before we wore masks, people would stop me in a grocery store or the airport and say, ‘Hey, you’re the guy who’s investigating the swamp on Oak Island . . .’

“People seem so invested,” says Spooner enthusiastically. “The least I can do is try to answer their emails and thank people for their interest.”

Having now appeared in 24 episodes, Spooner is listed on an internet movie database (IMDb) and spent two to three days a week in 2020, from May through November, on Oak Island.

Do not, however, confuse this for glamorous work. Research takes place from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. often in the heat and goo of the swamp. “For everyone, it’s a very long day and I’ve been known to get a bit testy,” confesses Spooner. “But when we’re all at dinner that night, or in the research centre discussing some new find, I see the camaraderie and co-operation it takes to do what we’re doing.

"It’s all about how people work together and how they share their ideas. It's not about confrontation, it’s about co-operation. There is a commitment to respecting each other and the different skills that everyone brings to the search. The hard work, respect and above all, perseverance that I saw around me has really made this experience rewarding.”

Spooner has also appreciated the chance to integrate his science into such a layered narrative. “I think being a professor and conducting research in small communities has really helped me feel more comfortable in this setting,” he explains.

“When you're a teacher or professor in front of a class, and you’ve got 200 people staring at you for an hour and a half, you must keep them engaged. It’s the same technique. I think that’s what’s made interacting with so many different people from so many backgrounds less stressful for me and maybe effective for those interested in what I am investigating.”

What's in store for 2021?

Will Spooner be back on Oak Island next year? If the search continues in 2021, the professor hopes to be back, but what Spooner is rooting for, eventually, is closure for the brothers, Rick and Marty. “What really went on there?” ponders Spooner. “It doesn’t have to be a treasure, but we are all committed to understanding what really happened on Oak Island, 226 years ago. I want the brothers to have answers.”

Should the mystery, someday, be finally solved, Spooner may return to relaxing evenings on Mahone Bay listening to Jimmy Buffet on his 28-foot sailboat. “The past two summers have been great, but hectic,” he admits. “By November, I am absolutely done. And I have responsibilities at school . . . I run a lab, write papers, work with graduate students. But one thing that keeps me going is that my involvement on Oak Island is finite. I honestly believe the research team is getting close to solving the mystery.”

When that happens, the grateful professor will still have his career, his family, boat, his band (he plays in a bluegrass band) to occupy his time.

“For years, I’ve told people that teaching at university is a bit like preaching to the choir,” explains the 59-year-old of his work as a professor. "But I’ve always tried hard to preach to the congregation." He says his work on Oak Island has been an “interesting environment for me to ply my trade. On Oak Island, I’m communicating with such a diversity of people, with so many different perspectives; it’s an opportunity I never dreamed I’d have.”