June 30, 2021

Sport & Calgary’s LGBTQ+ History

Organized sport has been and in many ways remains a complicated social space for LGBTQ+ persons. Participants’ experiences of overt and covert homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny (and intersections with colonialism, racism, ableism, and body shaming) are well documented in academic research as well as popular texts. Discrimination may take the form of so-called “locker-room talk” from other athletes, from coaches, from sport leaders and officials. It may also take shape through exclusionary and sometimes violent policies targeting transgender and gender-nonconforming persons. It is also present through expectations placed on individuals to perform gender in expected and privileged ways as well as through penalties for not doing so. At the same time, sport can be a space where LGBTQ+ persons experience community, empowerment, enjoyment, improved physical and mental health, and develop sport-specific skills. Interestingly, scholars such as Judy Davidson, Cathy van Ingen, and Travers, amongst others, have noted that sport teams and organizations created specifically for the LGBTQ+ community are themselves not free from exclusionary policies, practices, and expectations.

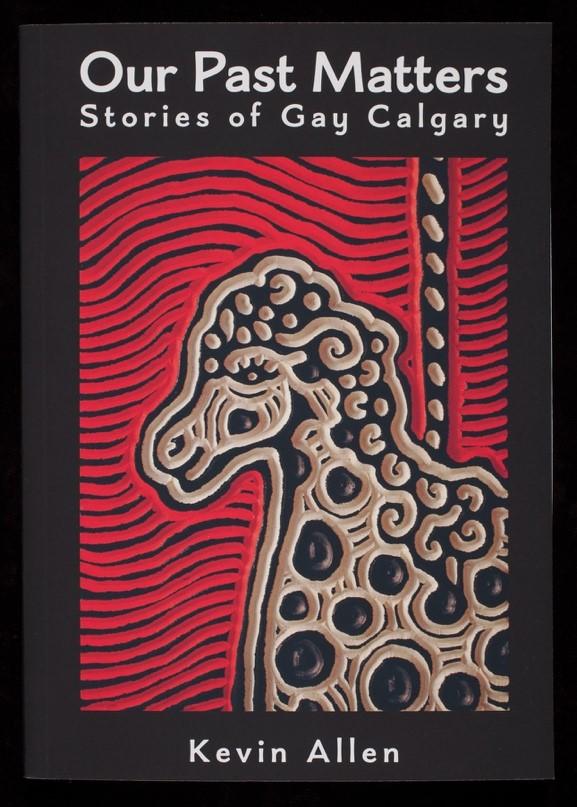

Cover art by Lisa Brawn. Etching of the Club Carousel logo.

In my project for the CIH, I am particularly interested in sport and Calgary’s LGBTQ+ history. The work draws heavily on Kevin Allen’s historical research, including his 2018 book Our Past Matters: Stories of Gay Calgary. Included in Allen’s work are stories about two predominantly lesbian softball teams that played games against one another beginning in the late 1960s, as well as the formation of Apollo in 1981, an organization established at least in part to help field a team for the 1990 Gay Games, which were being held in Vancouver. The present project also builds on work undertaken by University of Calgary alumnus Connor MacDonald and I, in which we explored the meaning of sport in the lives of LGBTQ+ Calgarians. From the interviews completed for that project, we found LGBTQ+ sport teams and organizations to be paradoxical: while providing safe spaces for many to express their sexuality openly (and for many, for the first time), they were not necessarily that inclusive of women nor of racialized Calgarians; while providing a space to pursue “better health”, ideas of healthiness were often connected to a particular body type; and, while promoting some sense of community, in focusing on competition versus participation, many were excluded (MacDonald & Bridel, 2020). The knowledge shared with us by the interview participants for that project was invaluable but also left me wanting to know even more about the history and in particular some of the connections between sport teams and organizations the participants alluded to.

And so, even more specifically than exploring sport and Calgary’s LGBTQ+ history, I am very interested in understanding how sport and physical activity intersected with other community groups and organizations in the latter half of the 20th century. What role might sport teams and organizations have played in an emerging activist movement? As Allen notes, Apollo was one of the community organizations involved in Project Pride Calgary, “an umbrella group of the city’s gay and lesbian organizations” who went on to produce “Calgary’s first Gay and Lesbian Pride Festival in June 1988” (p. 120). It was against a backdrop of political and cultural conservatism in the city, the province, and the country in which sport teams and organizations such as the Alberta Rockies Gay Rodeo Association, the Rainbow Riders Bowling League, the Different Strokes swim club, and the Calgary chapter of the Frontrunners formed. It was also against this backdrop where some LGBTQ+ Calgarians were participating in so-called mainstream sport leagues—and doing so openly.

It is imperative to recognize that in the early years of many of these sport teams and organizations, LGBTQ+ persons were still experiencing discrimination in the workplace and in familial lives, fear of gay bashing, police surveillance, the stigma of HIV/AIDS, lack of positive media representations, and opposition to their existence from religious and political groups. Allen’s work has been incredibly constructive in understanding the Calgary context; the work of other scholars such as Mary Louise Adams, Patrizia Gentile, Gary Kinsman, and Valerie Korinek provide a broader lens. Together, all tell a story of resilience and activism, a pushing back against a society that sought to deny our fundamental human rights, indeed our existence.

Through interviews and historical documents, I hope to add more about sport and physical activity to this story. To date, seven LGBTQ+ Calgarians have generously shared their stories with me. I continue to seek more participants who are willing to chat about their experiences in sport and physical activity sometime during the 1960s up to the early 2000s in Calgary. I can be reached at william.bridel@ucalgary.ca if you or someone you know might be interested in participating.

This is a project I have wanted to undertake for some time now and I am extremely grateful to the CIH for the opportunity to do so. It is important for me to recognize that the work of others has been so informative to my work to date. In addition to individuals named previously, I also have found research completed by Carolyn Anderson and Dawn Johnston to be insightful, both who explored Calgary’s LGBTQ+ history and uncovered information about sport or physical activity. Through my narrative inquiry, I am humbled to be able to make connections between what others have discovered and to add new information. I am honoured to help tell the stories that popular history doesn’t—the stories of the oppressed, of the marginalized, of the disenfranchised, but even more so the stories of those who fought in brave and various ways so that they, and those who followed, would be nothing less than equal.

Citations

Allen, K. (2018). Our past matters: Stories of gay Calgary. ASPublishing.

Anderson, C. A. (2001). The voices of older lesbian women: An oral history. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Calgary.

Johnston, D. (1999). Sites of resistance, sites of strength: The construction and experience of queer space in Calgary. Unpublished master’s thesis. University of Calgary.

MacDonald, C. & Bridel, W. (2020). A socio-historical exploration of gay sport and physical activity communities in Calgary. JURA, 8, 2-8.

Scholar-in-Residence Report

Petra Dolata, Associate Professor, Department of History

(Hi)Stories of Energy Transitions

The academic year 2020-21 was supposed to be a year of travel and archival research. Instead, it turned out to be a year of new beginnings and making new connections. During my research and scholarship leave I had envisioned to carry out further archival research in North America and Europe for my SSHRC-funded research projects on the 1970s energy crises in a transatlantic perspective and on Canada’s future energy relations with the EU and the UK after Brexit. However, the pandemic closed all archives.